EXCLUSIVE: “We’re making progress as an industry,” say Sachin-Jigar

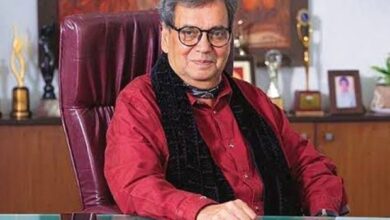

Stepping into Sachin and Jigar’s serene studio feels like entering a sacred space for music. The walls, painted in soothing shades of white and sky blue, complement the green sofas. Shelves lined with books on music reflect the duo’s passion and expertise. As I wait for my turn to speak with them, a beautiful voice echoes from behind a closed door, hinting at a rehearsal in progress. My thoughts are interrupted when a team member calls me into their inner chamber. Excited, I enter, eager to explore their creative process and hear their insights on composing, songwriting, and the evolving Indian music landscape. Our conversation reveals not only their artistic approaches but also their deep love for culture and ownership of their music.

You’re the go-to composers for horror, after creating songs for Stree, Stree 2, Roohi, Bhediya and Munjya. How do you avoid repetition when it comes to horror films?

Sachin: We’ve had our unsuccessful attempts too. For example, Roohi struggled because of COVID. We’re always blending genres. We can’t deliver 100 per cent horror; that would only attract a niche audience. Our songs need a mix of comedy and romance to appeal to families. Without the horror elements, only the masala works. The script helps us determine the right flavour for each song. A track like Kamariya wouldn’t fit in Munjya. Jigar and I don’t stockpile songs; we curate and customise them for the characters and the

movie’s premise.

Jigar: We knew the Stree universe would continue, so we avoided making sequels like Milegi Part 2 or Kamariya Part 2. We didn’t want to fall into the ‘part 2’ formula.

Is there a method to your madness when creating hooks for songs like Char baj gaye or Beat pe booty?

Sachin: It’s easier to discuss songs like Babaji ki booti or party tracks, even though we don’t party. We also write breakup songs, but we’re not looking to break up with our wives. As artistes, we adapt to whatever genre we’re given. If it’s a comedy film, we challenge ourselves to find a fresh approach. We don’t see song-making as a challenge, whether it’s dance or romantic music; we view it as creating pieces that bring joy. Lyricist Amitabh Bhattacharya once said, “Baaki sab theek, bas chal raha hai,” and I find myself saying that often. We try to capture inspiration from conversations, folklore, and everyday life. It’s not always easy but it’s definitely fun.

What I’m hearing is that this isn’t just a profession for you…

Jigar: Absolutely, it’s our passion. You can create a song without passion once or twice but not consistently. Interestingly, making a dance track is often harder than crafting a sad or a romantic song. Romantic or sad songs resonate with people’s lives, making them harder to critique. In contrast, dance songs often face criticism for being cringe.

Sachin: Creating a good dance track is serious business; it needs to connect with people. After Kamariya in 2018, we decided to avoid using the word daaru in our songs. We’ve explored every angle of partying, from Chaar baj gaye to Bababji ki booti. But how do you create a party song without the usual elements? We experimented with Taras and Aaj ki raat, which have no party references but are still lyrically fun and engaging. We’ve embraced the challenge of making people want to dance to these tracks.

Since you mentioned Kamariya, I’ve always wondered if you intentionally pronounced it as Komoriya because of the Bengali accent, or if it just happened.

Jigar: (Laughs) That’s definitely our choice!

Sachin: As someone from Kolkata, you know the dialect adds a lot of fun. For instance, Dance Basanti sounds much better than Naach Basanti. Instead of following trends or making our songs sound overly polished, we focus on incorporating authentic Indian elements, especially from the heartland.

Jigar: Saying Kamariya feels bland, but Komoriya or Nojoriya adds that extra flavour. And speaking of accents, the word Thumkeshwari has more impact when pronounced with an English twist.

Sachin: We might say darun in Bengali, but faata faati has a better ring to it. This reflects our approach. we believe in using folk elements that are deeply rooted and natural to us. Folk is in our blood. Put us in a setting with our favourite folk songs and we truly thrive.

Which are your favourite folk songs?

Sachin: Oh, I could name at least 500 songs from Gujarati culture alone. But it’s not just about the origin of the folk. If we were scoring a film set in Canada, we’d explore their folk traditions too. We aim to dive deeper into different cultures because folk is truly at the grassroots level. Once, we played Jaise mera tu from Happy Ending for Arijit Singh and decided not to include an interlude. Jigar suggested that Arijit sing it with an Irish twist. When Arijit asked if he should do a North Irish or South Irish accent, we were taken aback. I believe that any creative person benefits from learning about various cultures and their music and that’s the perspective we bring to our work.

We see a lot of commercialisation with the rise of K-pop, and discussions often revolve around ticket sales and performance videos. India seems to have few independent artistes. What’s your take on this?

Jigar: I think we’re making progress. Platforms like Spotify showcase many independent songs competing with Bollywood hits. But while we should celebrate our culture, we also need to evolve it. We must pass our culture to the next generation and let them draw inspiration from it.

Sachin: The main issue is that youth aren’t encouraged enough to embrace their own language or culture. For example, a Gujarati singer might get more recognition for a Punjabi song than a Gujarati one. Popularity shouldn’t be the only measure of success; that’s just a shortcut. True change involves ownership. It’s important to be proud of where you come from, saying, “I’m from Gujarat and I eat dhokla.” Punjabi songs are globally popular because Punjabis proudly embrace their language. This sense of ownership is often lacking in other parts of India and that’s something we need to change. As creators, we have to lead this change; I can’t just blame others for not doing enough in the Gujarati music scene.

Jigar: People in the South take pride in their culture. For instance, in Chennai, singing Suprabhatham in the morning brings joy. I can wear a lungi like Rajinikanth at award functions or weddings and no one will blink an eyelid. It’s crucial for people to embrace the swag in being themselves and take pride in their identity.

Why do you think Arijit Singh, despite being a major star, isn’t as globally popular as Taylor Swift or Dua Lipa?

Sachin: It really comes down to ownership. Can we elevate him to the point where he can sell out shows internationally? With 1.4 billion people, we have the potential to outnumber others. We need to embrace our culture, languages and music more. As parents, we need to teach our children to be proud of who they are. Look at why singing in Punjabi is considered cool. It’s all about the attitude. Artistes like Honey Singh and Badshah embody that pride and courage. We all need to step up and foster that same spirit.

How do you recognise which singer fits a song?

Sachin: It’s much like casting an actor for a story. The singer is the actor of the song and it’s a crucial decision. The film’s lead often has a say in the selection of the singer and may even recommend someone. We consider many factors when making that choice. As composers, we can introduce new voices, like we did with Varun Jain for Tere vaaste. Jigar always says you need to be in the right place at the right time with the right talent, and a bit of luck plays a role too. There have been instances where I thought the scratch versions of songs were better than the final products. Ultimately, producers also have a say because popular singers can help reach a wider audience. Today, we consume music largely through established artistes like Arijit Singh. So, it’s not just an artistic decision; commerce and popularity are significant factors too.

Jigar: Additionally, when there’s a void left by a singer like KK, whom we loved, it’s vital to find a new voice. There will always be a need for fresh talent to fill that gap.

Can independent singers make their way up?

Sachin: Collaborations between popular singers and newcomers often help make songs more appealing. New artistes from Punjab are also carving out spaces in our playlists. Singers like Prateek Kuhad and Anuv Jain have made a significant mark in the industry.

Do you think India needs more musicals like your own Rajadhiraaj and theatres that can accommodate them?

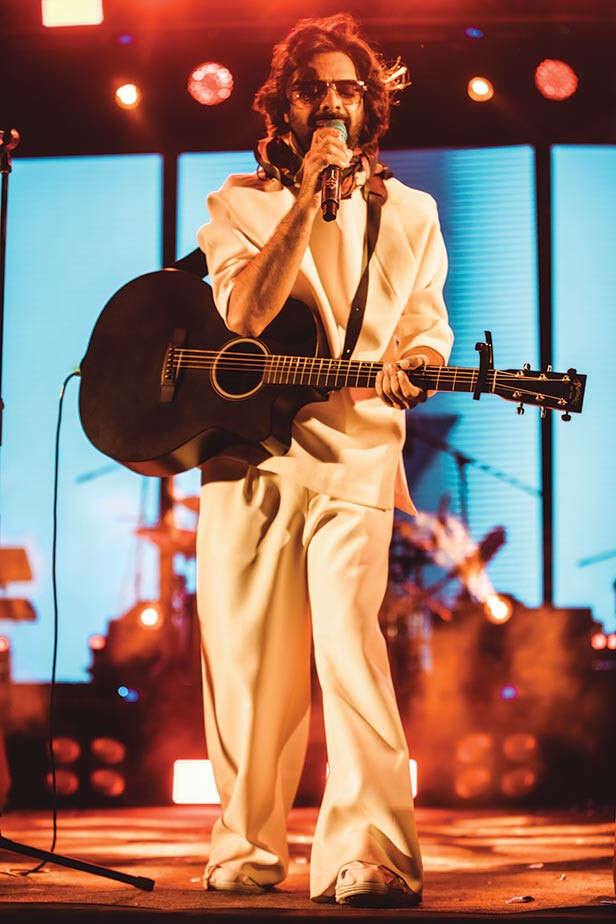

Sachin: Absolutely, this change has to come from the top. The NMACC theatre, where Rajadhiraaj is playing, is igniting a movement that will continue to grow. If we can prove the value of our work, these venues will emerge. They can’t charge high ticket prices without delivering exceptional entertainment. Theatre is our happy place as artistes; we’ve been involved in it for 20 years.

Jigar: Productions like Rajadhiraaj are significant undertakings. We need sponsors with the resources to sustain them. It’s important to present grandeur to the audience and show them live performances.

Do we have actor-musicians in India?

Jigar: Yes, we definitely have them.

Sachin: We’ve curated 20 names from a list of 60. There are actors who can sing and singers who can act. But that crossover isn’t easy for everyone. In Bollywood, for instance, Ayushmann Khurrana is a great example of someone who can truly sing. Jaaved Jaaferi and Shraddha Kapoor also have singing talent. When actors like Shraddha sing their own songs, it adds authenticity. Theatre is our life. After exploring various mediums, I find that theatre allows me to sleep peacefully at night.