The Republicans: A party born to fight slavery in America | Research News

On March 1, 1854, a small yet historic meeting took place in a schoolhouse in the village of Ripon in Wisconsin, United States. A group of individuals staunchly opposed to the expansion of slavery in the United States came together in protest against a bill being proposed in the Senate. The Nebraska Bill, as it was called, intended to open up Kansas and Nebraska territories to slavery. Opponents to the bill, mainly in the northern US states, saw it as aggressive and expansionist. At the Ripon meeting, some of them came together to resolve that “of all the outrages hitherto perpetrated or attempted upon the North and freedom by the slave leaders and their natural allies, not one compares in bold and impudent audacity, treachery and meanness with this, the Nebraska Bill.”

At this same meeting, they also resolved that if the Nebraska Bill were to pass in the Senate, they would throw away old party organisations and form a new party directly opposed to the bill’s principles of the bill. On March 3, the bill passed the Senate. It was viewed by its opponents as “expressly intended to extend and strengthen the institution of slavery”. They responded with a new party, founded intently to oppose slavery – the Republican Party.

Today, the party being represented by Donald Trump in the upcoming US presidential elections is largely associated with conservative values of white supremacy, anti-immigration, anti-abortion, and liberal gun laws – a long way away from the progressive ideals it was founded on.

American slavery and the Kansas-Nebraska Act

In the years immediately following the American War of Independence, slavery was a rather minor issue of debate. The economy of the southern states was largely based on slave labour. While the two major political parties of the time – the Whigs and the Democrats – agreed to let slavery in the South remain as it was, the practice came into discussion as America began expanding westwards and bringing more states into the Union. The issue of slavery was specifically a matter of concern for the northern states who feared that it would allow the South to gain political advantage in the government.

In 1820, a major legislation was passed called the Missouri Compromise. It prohibited the spread of slavery in the lands above the southern border of Missouri, which would eventually become the states of Kansas, Colorado, Nebraska, Wyoming, Montana, South Dakota, and North Dakota. This arrangement came under threat when Illinois Democratic senator Stephen A Douglas in 1854 proposed the Kansas-Nebraska Act which would overturn the Missouri Compromise and open up large swathes of land to slavery.

“Men across the north recoiled from this attempt to inject slavery into land that had been free for more than thirty years,” wrote historian Heather Cox Richardson in her book To Make Men Free: A History of the Republican Party (2014). The first to take a stand against this proposed legislation were the abolitionists who had been campaigning for the dissolution of slavery everywhere.

One such abolitionist, Horace Greeley, who was also the editor of the New York Tribune, argued that the bill was a political and economic threat to white men. As explained by Richardson, Horace argued that the Kansas-Nebraska proposal “proved that slave power had succeeded”. “What Southerners wanted, he wrote, was to control the government in order to push their economic system over the entire continent,” wrote Richardson adding, “According to Greeley, a slave power threatened to subvert American equality.”

The threat of the Nebraska Bill thus fuelled one of the biggest political realignments in American history, giving birth to the Republican Party.

Birth of the Republican Party

Soon after the Senate passed the Nebraska Bill, a second meeting was planned on March 20, 1854. Alvan Earl Bovay, one of the key founders of the Republican Party, said about the meeting, “I went from house to house and from shop to shop and halted men on the street to get their names for the meeting on March 20. 1854.”

In his book The Origin of the Republican Party, author A F Gilman noted that out of the 100 voters at that time in Ripon, 54 were secured for the meeting. They consisted of opponents of slavery from each of the extant parties at the time – the Whigs, the Democratic Party and the Free Soil party.

The discussion went on till the late hours. It ended with the dissolution of the town committees of the Whigs and the Free Soilers and a committee of a new party was established. It was named Republican by Bovay who believed that the name having been coined by Thomas Jefferson while founding the Democratic-Republican Party in the 1790s carried substantial historical connotations which would be held in reverence by the people of the United States.

The Nebraska Bill was signed into law as the Kansas-Nebraska Act by Democrat President Franklin Pierce on March 30, 1854. In the months that followed, several anti-slavery state conventions were held. Later, on February 22, 1856, an informal convention was held in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to form a national organisation by the name ‘Republicans’. They declared the purpose and objective of the party being an opposition to “the extension of slavery to free territory.” Among those present at this convention was Abraham Lincoln, who would later serve as the 16th president of the United States and be best known for his role in the abolition of slavery.

From anti-slavery to white supremacy

In the years following the birth of the Republican Party, slavery-related issues turned into heated topics of discussion and debates between states in the North and the South. The controversy came to a boil in 1860 when Lincoln won the presidential elections. The seven slave states of the South responded by seceding from the Union in fear of the threat his presidency would be to the institution of slavery.

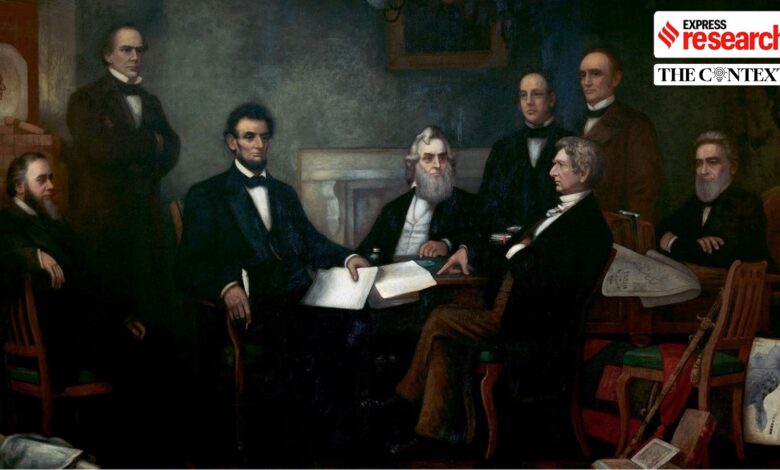

The secession of the South led to the American Civil War in 1861. At the onset, the aim of the northern states was simply to restore the South to the Union. As the war went on though, Lincoln and the Republicans were convinced of the need to free slaves as a way to undermine the southern opponents. Eventually, in 1863, Lincoln came out with his Emancipation Proclamation announcing freedom for all slaves in the states still under rebellion. “I never, in my life, felt more certain that I was doing right, than I do in signing this paper,” he is known to have said while signing the proclamation.

With the abolition of slavery in the Confederate states, the Union army enlisted several of the newly freed slaves. By the end of 1863, a large number of regiments in the Union army consisted solely of Black soldiers.

As the war came to an end by 1865, Congress approved the 13th Amendment, thereby banning slavery nationwide. In the years immediately following the Civil War, the Republicans emerged as a party that fought for the rights of the Blacks. They passed the country’s first Civil Rights Bill to protect the rights of all citizens irrespective of race or colour. They managed two big and radical amendments to the Constitution, including one establishing the right to vote for African-Americans.

However, this period of advocacy for Black rights ended very quickly for the Republicans. As Richardson noted, “as early as 1864 it was apparent that their economic policies were creating a class of extremely wealthy men.” In the years that followed, the party started losing its Black votes and by the 1950s itself, there were twice as many Blacks who sided with the Democrats as those with the Republicans – a trend that continued well into the present.