Zanjeer, Ardh Satya and Soni: The definitive cop trilogy that dismantles Rohit Shetty’s Cop Universe | Bollywood News

These aren’t cops; they’re supercops. Machismo seeps through their sleeves, heroism courses through their veins, and dialoguebaazi is their language. They are solitary crusaders, waging a battle against an unjust and corrupt system, prepared to go to any extent to restore order and normalcy. Any extent means any extent — even if it involves staging a fake encounter or custodial violence. They’re not just upholding the law; they are the law: rule-breakers with little regard for anything beyond violence. To them, violence is the path to justice, a response to the delays and inefficiencies that cripple the system. Violence then is both the means and the end, and their bravado the reigning norm.

No points for guessing — this is the formula of Rohit Shetty’s Cop Universe: a cinematic playground of big stars, bigger stunts, and the biggest cars. And now, the universe revs up for the Diwali release of Singham Again, easily one of the most anticipated films of the year and, quite possibly, the only major star-studded release in a year otherwise short on top-tier blockbusters. Shetty kicked off this supercharged saga over a decade ago with Singham and Singham Returns, led by Ajay Devgn. He then shifted gears with Simmba and Sooryavanshi, respectively, bringing Ranveer Singh and Akshay Kumar into the fold. Now, Singham Again rolls out as the grandest instalment yet, uniting Devgn, Singh, and Kumar alongside Kareena Kapoor Khan, Deepika Padukone, Arjun Kapoor, and Tiger Shroff. And just to keep things fresh, Shetty even ventured into OTT earlier this year with the series Indian Police Force, starring Sidharth Malhotra, Shilpa Shetty, and Vivek Oberoi — proof that he’s bringing the action everywhere, screens big and small.

A closer look at Shetty’s expedition into the world of cops reveals intriguing nuances. His cop characters swing between system defiers and enablers, caught in a constant tug-of-war between duty and self. Their narratives pivot around the drive to restore order, often by disrupting or destabilising the existing status quo. Beyond their rugged exterior lies a depth pushed by personal loss, an inner imbalance that sharpens their resolve and urgency to act. Peering beneath the surface one can also spot traces of these tropes in what I call the “Cop Trinity” — Zanjeer, Ardh Satya, and Soni — all artfully composed cop dramas. These films share some common ground with Shetty’s maximalist, formula-driven Cop Universe.

Also Read | Revisiting Prakash Mehra’s Zanjeer: The film that made Amitabh Bachchan

In Zanjeer, Ardh Satya, and Soni: the protagonists are lone warriors navigating a system inherently inefficient, and marred by red tape. Burdened by personal conflicts and familiar traumas, they are unremittingly driven to fulfil their duty with utmost sincerity. Above all, they are vessels of frustration and rage — rage against the establishment, their own pasts, and a society seemingly beyond redemption. In this sense, Shetty’s cops appear as close kin, cut from the same cloth, speaking the same language, and waging the same battles. But, it is precisely in their differences that these seminal films stand apart, confronting Shetty’s Cop Universe and offering a contrasting, and eventually deeper perspective.

Ajit, Bindu and Amitabh Bachchan in Zanjeer. (Express archive photo)

Ajit, Bindu and Amitabh Bachchan in Zanjeer. (Express archive photo)

Within the first fifteen minutes of Prakash Mehra’s genre-defining Zanjeer, the ever-reliable Iftikhar, portraying the superior to Amitabh Bachchan’s newly appointed cop, Vijay, elucidates the critical importance of upholding law. He critiques Vijay’s brazen transgressions, highlighting the dangers of taking justice into his own hands and rendering the system a mere mockery. In a well-crafted long take, Iftikhar articulates the paradox of police power: while Vijay wields considerable strength, this power comes with significant responsibilities. He may possess the freedom to exert it, but he must remain aware of the consequences that accompany such actions. Though Iftikhar’s admonitions may appear didactic, their fundamental message connects deeply within the framework of police procedurals. After all, if those entrusted with maintaining the law abuse their power and flout its boundaries, where then can the citizenry turn for justice?

While it may appear that the lineage of cops gracing the screen today has drawn heavily from Salim-Javed’s iconic Vijay in Zanjeer — including those crafted by Shetty — the reality is that none have truly wrestled with Vijay’s internal struggles, with his own rage and machismo. Many have adopted his bravado to disrupt the established order, but they overlook the intense truth that he is severely punished by the very system he defies to protect. The irony here is both incisive and biting: the institution you try to uphold dismisses your spleen, toys with your masculinity, and eventually ridicules your bravado. It punishes you until you either concede or become a complete outlier, rendered vulnerable to lawful retribution. This subtext, rich in complexity, is one that Shetty seldom dares to explore, which perhaps explains why his portrayals of cops often gravitate toward the straightforward — and consequently, mundane.

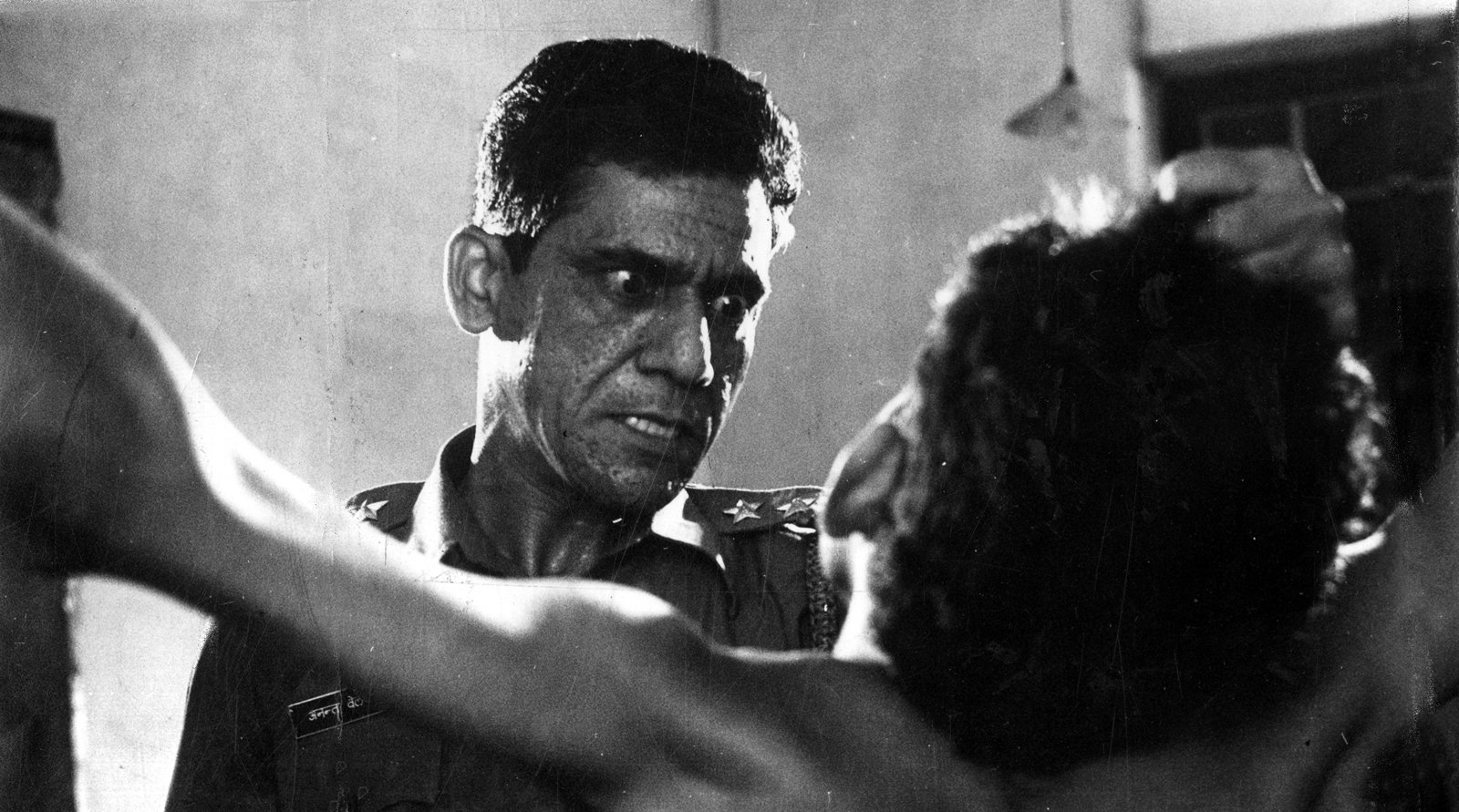

Om Puri in Govind Nihalani’s Ardh Satya. (Express archive photo)

Om Puri in Govind Nihalani’s Ardh Satya. (Express archive photo)

But the one who truly grasped this complexity and built upon it was Govind Nihalani with Ardh Satya, released exactly a decade after Zanjeer, and regarded as the ultimate cop film of Bombay cinema. Its protagonist, Anand (Om Puri) — is an idealist cop who, despite his struggles, eventually succumbs, becoming part of the very system he once sought to challenge. So he begins deriving a perverse high from channelling his inner violence and justifying it in the process. He exists within the system yet finds himself abandoned by it. His work transforms into an excuse for battling with his own troubled past, perpetuating the cycle of violence. Even in his attempts to do good, he cannot escape participation in injustice, often left helpless in this chakravyuh of power and morality.

This predicament compels him to question his own abuse of power and whether the violence he instigates will ever lead to the downfall of the corrupt structures he opposes? And if they do, do they not give rise to new ones? Then what is the purpose behind his vigilantism? In that sense, his journey consequently led to the death of his conscience. To drive this point home: Nihalani questions unchecked police brutality and the hypermasculine desires that manifest it in the name of justice. This is further examined in great depth in Ivan Ayr’s brilliant police drama Soni. It’s almost surreal how a response to a key scene in Ardh Satya exists in Soni, which was released nearly 35 years later.

Also Read | Remembering Om Puri: Unlikely hero who straddled twin worlds of Ardh Satya’s Anant and Narsimha’s Baapji

In Ardh Satya, Anand articulates his frustrations and rage toward a man who harasses Jyotsna (a superb Smita Patil), asserting that individuals like him deserve to be eliminated on the spot. In contrast, Soni features an intriguing scene in which the policewoman Kalpna (masterfully restrained Saloni Batra) recounts a childhood memory of witnessing a group of policemen mercilessly beating a man who had harassed a woman. Despite recognizing the gravity of his offence, Kalpna couldn’t help but sympathise with the man and felt anger toward the police personnel for their incessant violence. Soni takes this even further, contrasting the world of Shetty’s hyper-masculine cop sagas with a grossly different portrayal: police officers who, though perceived as wielding power, are treated as second-class citizens. In uniform, they are expected to suppress their emotions, maintaining objectivity even as they work within a system designed to undermine them.

The anger that defines the titular character (Geetika Vidya Ohlyan), isn’t directed at the rule of law itself but rather at those who manipulate it to reinforce misogyny. It’s captivating how, despite being part of the force, both Kalpana and Soni serve as law enforcers but remain vulnerable to the very crimes they confront. Here, violence is almost incidental: no character seeks it, nor do they revel in it. Kalpana repeatedly questions the moral choices Soni makes, probing the roots of her rage. It’s as though she understands that the system will never honour Soni’s defiance, so she guards her.

In the broader narrative arc of this cop trilogy, actions carry weight and consequences. Accountability is inescapable, even if the characters don’t desire it. They are confronted and questioned, often to the point of humiliation. Here, violence is neither the means nor the end — it’s a reaction they themselves despise. This is precisely where Shetty’s Cop Universe falters. Beyond its overt glorification, it moves away from diving into the complex lives of its characters in uniform, opting instead for quick resolutions to even simpler conflicts. Violence isn’t questioned or restrained: it’s embraced, practised, and celebrated without reserve. The system doesn’t punish; it rewards. No one dares to question the authority of these officers, for in this universe, wearing the uniform implies inherent righteousness. But does authority alone absolve them of accountability?